August 20, 2015

By Craig Boddington

The first bighorn ram I ever saw was on top of one of the highest points in Montana in a place called Froze-To-Death Plateau. That's almost what happened to us trying to get to him, and we almost got a shot. Almost, but not quite.

A rough, high, frigid place like that is where we expect to see the Rocky Mountain bighorn€¦but that's actually our fault or at least the fault of our ancestors.

The bighorn sheep is perfectly at home in the high country and was certainly never a creature of the plains, but his most natural habitat are hills and breaks rather than true mountains. When European settlers started pushing west, it is believed bighorns occurred in the low millions all across the Rocky Mountain Front and westward across the Sierra Nevada.

Advertisement

His tender, flavorful meat was (and is) highly prized, and without question, he was overhunted during our settlement era. But the greatest reduction in numbers probably came from exposure to domestic sheep, which carry diseases that are devastating to wild sheep. By the turn of the last century, only remnant populations remained, pushed into the highest and harshest country where hunters might tread but shepherds would not.

Although biologists are not totally in agreement, we hunters divide bighorn sheep, Ovis canadensis, into two categories: bighorn sheep and desert bighorn sheep. The latter is a smaller-bodied adaptation of the Southwest. The bighorns are usually considered to have occurred in three races: the true Rocky Mountain bighorn, the slightly smaller California bighorn or Sierra Nevada bighorn, and the Badlands or Audubon's bighorn.

Audubon's bighorn, considered extinct since 1925, was the sheep of the Black Hills and the breaks and bluffs of the western Great Plains. Proving that the bighorn sheep is not necessarily a creature of the high country, Rocky Mountain bighorns have been successfully introduced (and are thriving) in western Nebraska, the Dakotas, and Montana's Missouri Breaks.

Advertisement

Today, the Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep is the most numerous and widespread. The California bighorn has not done as well, but it persists in sustainable populations from northern California northward to British Columbia.

The primary reason for the survival and continuing increase of the bighorn sheep is incredible effort on the part of hunter-based conservation organizations, with the Wild Sheep Foundation the driving force. Habitat projects and relocations, funded by hunters, have increased sheep populations more than 400 percent since 1960.

I have hunted Rocky Mountain bighorns in Montana's incredibly rough "unlimited permit" areas, Wyoming's high country east of Yellowstone, and in the gentle sagebrush hills of southwestern Montana's low Pioneer Mountains. Overall success was just 50 percent, but each bighorn hunt was a special experience.

Natural History

North America's wild sheep crossed over from Asia on the Bering Strait land bridge during the Pleistocene, about 750,000 years ago. Eventually, they spread from Alaska down through British Columbia and the Rocky Mountain chain all the way to northern Mexico.

Their closest relative in Asia is the snow sheep of Siberia. But divergence from Asian sheep began about 600,000 years ago, and over the millennia, American sheep diverged in turn, with the "thinhorn" Dall and Stone sheep occupying the northernmost ranges while the developing bighorns spread on southward.

The Rocky Mountain bighorn is a stocky animal with mature rams weighing more than 300 pounds. As such, he is one of the largest-bodied of the world's wild sheep, heavier than many of the longer-horned argali sheep of central Asia. His horns grow around a central core, and he is aptly named; his horns can be 18 inches in circumference at the base, and the weight of the horns alone can exceed 30 pounds.

Length is not extreme because, unlike sheep with more flaring horns, the bighorn typically rubs down or "brooms" his horn tips. Theoretically, this is because they obscure his vision, but despite extreme mass, few bighorns exceed 40 inches around the curl, while the biggest thinhorns often do, and some varieties of Asian argali can exceed 60 inches.

Ewes are generally about a third smaller and have short, rudimentary horns.

Bighorns are generally brown in color, and at first blush it would seem that they are extremely well-camouflaged. This is partly true, but the giveaway is the white rump patch. As they turn while feeding, that rump patch almost seems to glow and through good optics is highly visible even at great distances.

The rut is usually November when the rams clash with the famous head-butting ritual — the crashing resounding through the mountains. The gestation period is six months, with one and occasionally two lambs born in May. The mating ritual is extremely hard on rams, with normal lifespan nine to twelve years; ewes typically live several years longer.

Shooting and Shot Placement

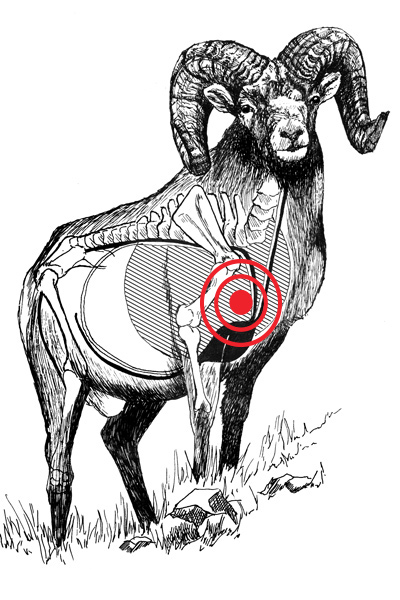

Although bighorns are large and strong, wild sheep are not especially hardy, definitely not as tough as most goats. Obviously, you want to hit them well, as any wounded mountain animal can go into stuff too steep and dangerous for recovery.

Although bighorns are large and strong, wild sheep are not especially hardy, definitely not as tough as most goats. Obviously, you want to hit them well, as any wounded mountain animal can go into stuff too steep and dangerous for recovery.

But if properly hit in the heart/lung area, even the biggest ram should succumb quickly. Large calibers are not necessary, but considering the scarcity of opportunity, the rifle and caliber chosen should be capable of handling any reasonable shot.

As Jack O'Connor advised, the .270 Winchester is a great place to start. Any of the fast 7mms will do just fine, likewise the fast .30s. But for sheep, the best results will be obtained with an aerodynamic bullet that expands fairly quickly.